In 2020, a paper that surprised many in the medical community was published. Published in The New England Journal of Medicine in December 2020 during the height of the COVID pandemic, the paper found that Black patients had nearly three times the frequency of missed hypoxemia (i.e., low oxygen levels) that was not detected by pulse oximetry compared to white patients. The paper sparked more research and deeper scrutiny on pulse oximeters — were these devices leading to worse health outcomes for patients with darker skin pigment?

In response, UCSF launched the Open Oximetry Project in 2022. Led by the UCSF Hypoxia Laboratory and the UCSF IGHS Center for Health Equity in Surgery and Anesthesia (CHESA), the project was created to improve the safety and precision of pulse oximeters in all populations by bringing together oximetry experts, engineers, academic researchers and other stakeholders from around the world.

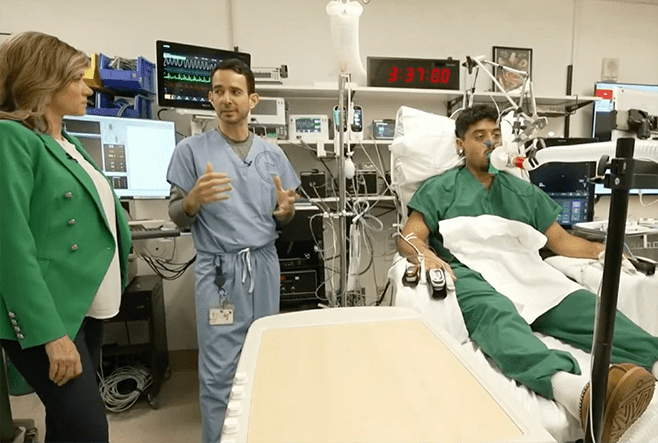

“Pulse oximeters are an essential medical device,” said Mike Lipnick, MD, the primary investigator for the Open Oximetry Project and professor of clinical anesthesia at UCSF, “but some unresolved scientific questions about them still need to be answered.”

New Results Show All Oximeters May Not Be Equal

Since the highly publicized paper came out in 2020, there has been a general perception that all pulse oximeters are faulty for people with darker skin pigment. Recent lawsuit settlements by oximeter manufacturers, including Medtronic, have perpetuated this attitude. However, that may not be entirely accurate, and the issue may be more complex.

For the past two years, Lipnick and colleagues have conducted extensive lab tests to determine how well different oximeters work and develop new protocols to better evaluate their performance. While manufacturers must only test the devices in 10 healthy people before submitting data to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Open Oximetry Project has tested each oximeter in up to 50 people of varying skin types, body types, gender and more. The results they’ve found from the testing, which are publicly available online, are mixed.

“The assumption was that all pulse oximeters have this problem, and the problem is always falsely about reading,” Lipnick said. Among the nearly 30 devices his team has tested, however, “we do have some preliminary evidence that suggests that there are some devices available on the market that either don’t have the problem or don’t have it to the same degree.”

These mixed results pose a new question for Lipnick and his team: Are there actually pulse oximeters on the market that work well on darker skin pigments, or have they just not done enough testing yet?

Open Oximetry Expands in Uganda

To answer this question, the Open Oximetry Project is working to open a new pulse oximeter testing center in Uganda. So far, Lipnick said, most data on pulse oximeter performance have been collected by labs in countries with predominantly lightly pigmented populations. Opening a Hypoxia Lab in Uganda will help provide a better snapshot of how pulse oximeters work in a diverse population.

Ronald Bisegerwa, MMed, an anesthesiologist and current CHESA fellow helping to establish the Hypoxia Lab in Uganda, says there are multiple benefits to having a testing center in-country. “The project will collect data relevant to low-resource settings and provide critical insights into how oximeters function in populations with darker skin tones, severe anemia and other unique challenges,” he said.

The Open Oximetry team also hopes that the new Hypoxia Lab in Uganda will improve the representation of low- and middle-income countries in the regulatory bodies that oversee the development of new standards for pulse oximeters. “This whole regulatory discussion has been predominantly focused on high-income countries,” Lipnick said, “representation of low- and middle-income countries has been entirely lacking or has been very marginalized.”

He hopes that collaborators from Uganda can work with the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). This global standard-setting body provides common standards for technology, agriculture, healthcare and other manufactured products, including pulse oximeters. While the FDA makes guidelines for devices sold and used in America, the agency often references ISO standards. “If these committees had been more diverse 10 or 20 years ago, would this problem even exist now?” Lipnick wondered.

The Open Oximetry Project is also collecting data for a new study that will characterize the diverse range of global skin colors. “We hope that the information gathered from this study will be used to inform future research and advocacy efforts on medical device validation standards that can be impacted by skin color, including the pulse oximeter,” said Elizabeth Igaga, MD, a member of the Open Oximetry Project and anesthesiologist at Makerere University.

New Guidelines Must Strike a Careful Balance

Despite a flurry of new research from the Open Oximetry Project and other groups, the ISO and FDA have not yet released updates on new guidelines for pulse oximeters. The FDA previously said that new guidelines for the devices would be released by the end of September 2024, but the agency recently pushed the release date back to sometime in the fiscal year 2025.

When those guidelines do come, Lipnick said, there is some concern that if not done carefully, they could cause access issues for patients in low- and middle-income countries. Pulse oximeters have an incredibly wide range of prices, from $2 to more than $8,000. In low- and middle-income countries, which often face budgetary constraints or rely on donations, low-cost devices are most common. Lipnick said these low-cost devices are usually, but not always, lower quality. If the ISO decides to publish new guidelines based on the health disparities that are occurring in high-income countries, it could mean that many pulse oximeters in low- and middle-income countries become non-compliant.

“With regulations being tightened or changed, this could create problems in the market that end up reducing access to quality pulse oximeters for poor communities,” he said.

For example, the cost of compliant pulse oximeters could increase substantially, and the number of oximeters on the market might decrease. High-income countries could easily weather these market changes, but for low- and middle-income countries, this could mean they cannot purchase pulse oximeters at all.

This careful balancing act — ensuring that pulse oximeters are safe for people with darker skin pigments while not constricting the market — is another reason the Hypoxia Lab hopes to involve more people from low- and middle-income countries like Uganda in the regulatory committees and discussions. “This initiative aims to bridge global health disparities and ensure equitable access to safe and effective pulse oximeters worldwide,” Bisegerwa said.

Photos: screenshots from NBC News story filmed at UCSF (January 18, 2025 broadcast)