Have you ever stopped to wonder how people develop the skills and character to do on-the-ground work through international groups like the UN, the Red Cross and Doctors Without Borders? How does a person come to speak multiple, often uncommon, languages, and have policy expertise and the capacity to travel constantly, witnessing immense human suffering without burning out?

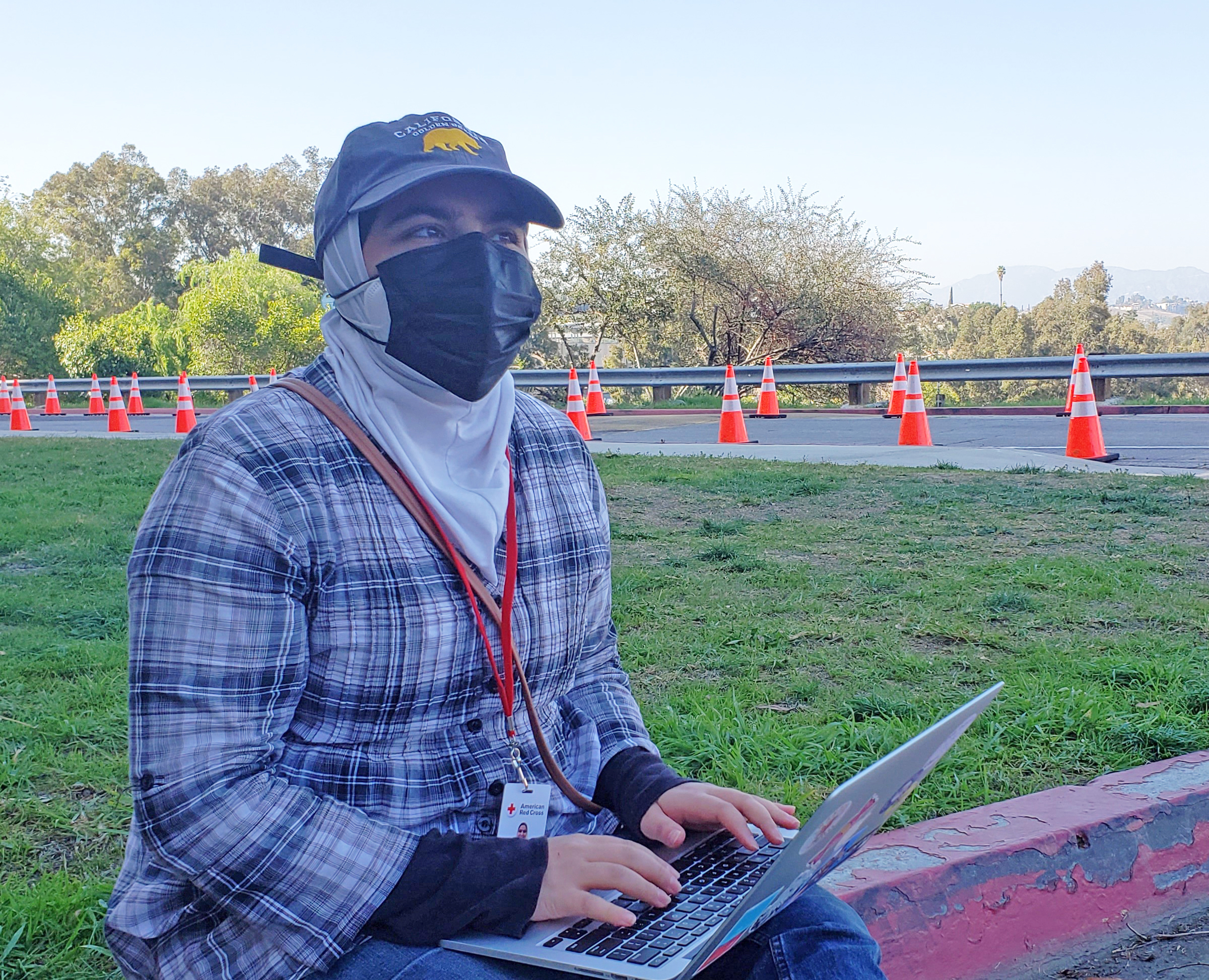

Ola Alani, a 2017 alumna of IGHS’s master’s program, seems to have the right stuff.

Born in Baghdad, Iraq, in the early 90s, Alani grew up amid the violence surrounding the U.S.-led war there. Alani was especially distressed when violence cut off her access to education. When she was 15, Alani’s family fled Iraq, eventually settling in California. Alani got into UC Berkeley – no small feat – where she was drawn to a popular minor, Global Poverty and Practice. The minor analyzes poverty, wealth, and inequality in an historical and global context. Alani majored in biology.

After graduation, Alani began volunteering at the Red Cross. She worked in the Restoring Family Links program, one of the NGO’s oldest, in which different branches of the Red Cross or Red Crescent work together to reconnect families who have been separated by a war, natural disaster or another humanitarian crisis.

Looking to finetune her focus, Alani was drawn to the master’s program at IGHS. She hoped to work with Fatima Karaki, MD, who runs the Refugee and Asylum Seeker Health Initiative. Karaki grew up in Lebanon and first learned of the Syrian refugee crisis – now in its 10th year – when people fleeing the violence in Syria began camping on her family’s farm there. The mentoring match was made, and Alani traveled to a major Syrian refugee camp in Lebanon for her capstone project, studying the residents’ barriers to health.

The barriers were numerous, and talking to the refugees about their experiences wasn’t easy. Alani had some experience at the Red Cross under her belt and had further prepared for her capstone research by taking a psychology course at UC Berkeley focused on interviewing victims of torture. Even so, Alani was at times overwhelmed by what she heard.

“You’re never 100 percent ready,” Alani said.

Alani has clearly established a wheelhouse of skills and interests, but she’s still looking for just the right niche to make her mark.

“I want to work with people who have experienced some form of displacement – it could be in the health context or the humanitarian context,” she said.

In 2020, she signed up for AmeriCorps, a national program which embeds volunteers in nonprofit organizations to help support community. With her previous experience at the Red Cross, Alani was placed there. Now she trains volunteers to do interviewing for the Restoring Family Links program and serves as a case worker for people using the service.

There are regular reminders of Alani’s own traumatic experiences living through a war, but it’s healing to be there for others.

“Even when I can’t provide a particular service, I can let them know that they’re not alone; there’s somebody to listen who cares,” she said.

If Alani winds up working on behalf of displaced people for a major NGO like the Red Cross, it will be mainly thanks to her determination, her preparedness, her people skills and her fluency in Arabic. Her M.S. will help, too.

“Of all the things I learned at IGHS, it’s the culture of humility that’s helping me most. I talk to people from around the globe, and I look into the person’s culture beforehand so I’m informed on how to work for them. I learned to listen, not judge certain aspects of the culture of the way they’re approaching the problem. My mind doesn’t go ‘Why is it this way?’ I’m looking for a way to help,” she said.